What’s the Difference: Distinguishing SPNEC from Solar Philippines and Solar Para sa Bayan

- January 19, 2026

- 0

The Department of Energy (DOE) announced recently that it is pursuing approximately P24 billion in penalties against Solar Philippines Power Project Holdings, Inc. (SPPHI) for failing to deliver on 33 renewable energy service contracts, representing over 11,000 megawatts of committed capacity.

The enforcement action, disclosed by Energy Secretary Sharon Garin during a January 13 press briefing, has prompted market confusion due to the similar naming conventions of several entities founded by Batangas First District Representative Leandro Leviste.

The publicly listed SP New Energy Corp. (SPNEC), now majority-owned by Meralco PowerGen Corporation (MGEN), has moved swiftly to clarify that it is not the entity facing the multi-billion peso sanctions. In a disclosure to the Philippine Stock Exchange dated January 14, SPNEC stated unequivocally that it “is not the ‘Solar Philippines’ mentioned in the news articles,” affirming that Solar Philippines Power Project Holdings, Inc. is a separate corporate entity.

Founded by Leviste in 2013, Solar Philippines Power Project Holdings, Inc. (SPPHI) is a privately held renewable energy developer that secured numerous contracts through the DOE’s Green Energy Auction Program (GEAP). According to Secretary Garin, the company accounted for approximately 64 percent of all terminated renewable energy service contracts in 2024 and 2025—some 11,427 MW out of a total 17,904 MW of canceled capacity.

“What we want are really legitimate investors that have the financial, technical and legal capacity to embark on a contract and an energy project in the Philippines,” Garin stated during the briefing, emphasizing that the DOE had issued multiple show-cause orders and notices to SPPHI without receiving any response.

The P24 billion penalty comprises performance bonds, contractual obligations, training and development funds, and other financial responsibilities embedded in the revoked contracts.

Many of these projects had final completion deadlines of December 25, 2025, which passed without any groundbreaking or construction activity. The DOE has referred the matter to the Office of the Solicitor General and the Department of Justice for appropriate legal action.

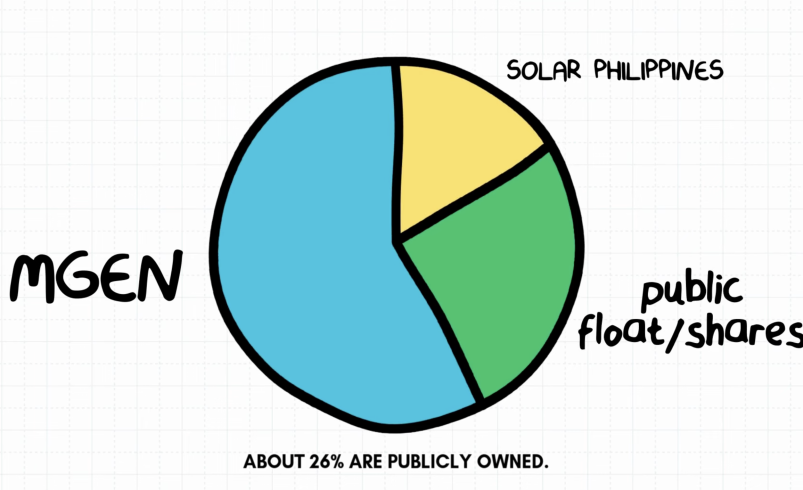

In contrast, SP New Energy Corp. (PSE: SPNEC) is a publicly listed company that has undergone a significant change in control since 2023. Through a series of transactions completed in October 2025, Manila Electric Company’s power generation arm, MGEN, acquired a 57.33 percent stake in SPNEC through its subsidiary MGen Renewable Energy, Inc. Leviste’s ownership has since decreased to 18.66 percent following the sale of 14.61 billion shares to Meralco for over P18.26 billion.

SPNEC is the developer of MTerra Solar (also known as Terra Solar), the world’s largest solar-plus-battery storage project currently under construction. Located in Nueva Ecija and Bulacan, the project will have 3,500 MW of installed photovoltaic capacity and 4,500 MW of battery energy storage once fully commissioned.

In March 2025, UK-based investment firm Actis completed its acquisition of a 40 percent stake in MTerra Solar for approximately US$600 million—the largest foreign direct investment in a single greenfield infrastructure project in the Philippines.

Secretary Garin herself has distinguished between the two entities. In a January 15 interview, she confirmed: “As to the performance of SPNEC, maganda yung performance ng SPNEC because I’ve been updated by Meralco constantly, and they ask for help whenever they have a problem. I know they are on track… this is a compliant company.”

MGEN issued its own statement clarifying that it “did not acquire any share in SPBC” (Solar Para Sa Bayan Corporation) and that SPNEC’s operations “are not dependent on SPBC’s franchise.” The company emphasized that all transactions related to SPNEC have been “scrutinized and approved by the Philippine Stock Exchange and the Securities and Exchange Commission.”

A third entity adding to the naming confusion is Solar Para Sa Bayan Corporation (SPBC), which holds a congressional franchise under Republic Act No. 11357, signed into law on July 31, 2019 by then-President Rodrigo Duterte.

This franchise grants SPBC the nonexclusive right to construct, install, and operate distributed energy resources (DERs) and microgrids in remote and underserved areas across 17 provinces and select municipalities, including parts of Batangas.

Unlike SPPHI and SPNEC, SPBC operates under a specific congressional mandate to electrify remote, unviable, and unserved communities using renewable energy technology. The franchise is valid for 25 years and is subject to regulatory oversight by the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) and the DOE pursuant to Republic Act No. 9136 (EPIRA) and Republic Act No. 9513 (Renewable Energy Act).

The DOE has confirmed that the terminated contracts pertain to SPPHI and “do not involve affiliated companies Solar Para Sa Bayan Corp. (SPBC) and SP New Energy Corp. (SPNEC).”

The DOE’s enforcement action against SPPHI reflects a broader crackdown on nonperforming developers as the government pursues its renewable energy targets under the Philippine Energy Plan 2020-2040. The Philippines aims to increase the share of renewables in the power generation mix from approximately 22 percent today to 35 percent by 2030 and 50 percent by 2040.

“Land and grid access are limited,” Secretary Garin noted. “Our responsibility is to make sure these resources produce power, not just plans.”

The reallocation of the 11,427 MW of terminated capacity to qualified developers will be critical to keeping the country’s energy transition on track. The DOE is now considering whether to place the revoked project areas under an open and competitive selection process, allowing new bidders to take over dormant developments.